https://swarajyamag.com/commentary/indias-state-emblem-has-fangs-2

Welcome 2021

2020 has profoundly affected almost everyone. As WFH and masks have become norms, what areas of your life have affected you? Here are some of mine.

Goodbye travel – Had to cancel two planned vacations this year, one overseas. Thankfully the airline fees were refunded. Looking forward to some travel in 2021 after a year in hibernation.

Goodbye gym – My gym membership lies mostly unused this year, and unlikely to be used in the near future (six months?) I may discontinue future subscription, condition to setting up better equipment and more consistent routines at home.

Goodbye MSM – My faith in MSM had been steadily dwindling over the years. This year I pulled the plug. I no longer read online news as first source of information. I prefer social media (read Twitter) as primary source. At least there’s no pretense of passing off opinions as facts.

Goodbye China – As a consumer, checking country of origin was something I rarely did earlier. Now I go out of the way to not buy anything significant that’s made in China. This is hard, sometimes impossible, and not worth it for low value goods. But I’m determined to send less money to a lying, deceitful totalitarian regime.

Goodbye TV –In the initial days of the pandemic, as I was still digesting the pattern of staying home for recreation, binge watching TV series became a major source of entertainment. Then read more books instead. Amazing number of hours are wasted watching useless stuff. Time is better utilized reading, writing, learning, pursuing something for your own growth. But be picky in what you read. There’s a lot of garbage published that’s not worth your time. Find an area of interest and read the best authors.

Words of advice for 2021 and beyond

- Save yourself from disinformation. Be vigilant of news media – take every piece of information with generous grains of salt; validate and cross check facts with multiple sources before you form an opinion. Challenge the so called guardians of truth. You’ll be surprised at what lies beneath their facade

- Take risks – not blindly, but avoid being a scared deer.

- Remain invested – After the initial shock from the pandemic, markets have recovered with healthy returns for portfolios that remained invested. Have a long term view. To quote Peter Lynch in context of an earlier era –

“I’m fully invested—before and after this extraordinary rebound. I’m always fully invested. It’s a great feeling to be caught with your pants up.”

- Be positive. And cautious. The virus is here to stay. But eventually it will be no more dangerous than the flu. The time-span could be a year, perhaps two. In the meantime we’ll ratchet back our existence to normal levels, hopefully with alertness, wisdom and good spirit. Here’s to 2021!

National Museum, New Delhi – Bronze Gallery

Established in 1949 and opened in 1960, the National Museum in New Delhi houses more than 210,000 art objects representing over 5,000 years of Indian art and craftmanship. With twenty five galleries spread across two floors, any serious attempt to truly take in and appreciate what the museum has to offer requires more than one […]

National Museum, New Delhi – Bronze Gallery

Deux hommes dans la ville (Two men in town)

Gino Strabliggi, a convict put away for twelve years for an armed robbery in Paris, is granted early release, thanks to his social worker counsel Germain Cazeneuve, who vouches for his safe conduct upon return to normal society. The two develop a friendship, as Strabliggi attempts to make an honest living. He is on the right path, and turns down his old buddies who attempt to lure him back to a life of crime. Even the accidental death of his longtime girlfriend Sophie in a car crash cannot deter him, and he re-locates to Montpellier, where Cazeneuve himself moved, to find work in a printing press. He also finds a new girlfriend, Lucy, who loves him, and wants to get married. Things seem to be going well for him, until chief inspector Goitreau, who had initially put Strabliggi behind bars in Paris, is also posted to Montpellier. He is a vindictive man, convinced that Strabliggi’s life as an ordinary citizen in only a cover for his next criminal act. Believing that a criminal cannot change, Goitreau continues to hound Strabliggi. Eventually, Strabliggi kills Goitreau in a tussle when he confronts Goitreau in their apartment while Goitreau was trying to coerce Lucy. He is tried for murder.

Director Jose Giovanni shot the film in languid frames with occasional big close ups. Music by Philippe Sarde, reminiscent of a mellow Italian serenade, fits in well with the narration and pacing. Alain Delon and Jean Gabin turn in believable portrayals of Strabliggi and Cazeneuve, Delon in particular capturing the intensity and magnetism of the Strabliggi character with authenticity. The film is a commentary on the degrading prison environment of seventies France, and maintains a critical outlook of the justice system in general. Germain Cazeneuve’s monologue creates the backdrop of the story, which traces the failed attempt of an ex-convict to resume life as a normal citizen, and his own struggles as a social worker in the prison system that is brutal towards its inmates. As Strabliggi tries to stay afloat, Cazeneuve, nearing retirement himself and frustrated with the system, takes up a different job consulting ex-convicts in Montpellier. Cazeneuve’s views are a stinging critique of the justice system that does little to help, in fact ostracizes, ex-convicts. Despite things going his way for a while, Strabliggi, eventually succumbs, and not entirely due to his own doing. He was “simply unlucky” – as Cazeneuve says in Court, when called up for his statement. He reminds the court that –

“Justice must be fair, but not fierce, it must fully understand the person it is trying, the crime and its reasons.”

He argues, that it was fate that led Strabliggi to an officer of law determined to bring him down, and that the sentencing should be considerate of the fact. However, mitigating circumstances are ignored, and Strabliggi is sentenced to death. A plea for clemency to the President of France is also turned down, and Strabliggi faces the guillotine.

A startling revelation, for me, was the use of guillotine for execution in the modern era. Thankfully, that practice came to an end in 1981, when France abolished the death penalty.

Rely first on your instincts

In the India of the eighties, where I grew up, “rank” in class was important. Rank meant one’s academic position in class, an index of one’s score in the progress report. It meant stature. It probably still does. The title of “first boy” or “first girl” was a badge of honor, a halo of prestige to inspire awe – in students, teachers and parents. Rank was inflated to be a measure of one’s worth.

However, it wasn’t a realistic measure. Creativity, for instance, took a back seat. Tests were not designed to gauge one’s organic ideas, rather the ability to learn by rote and apply it to a fairly limited set of patterns. In the subjects of languages and literary arts, where seeds of original thought are probably most easily sown, a tendency to rehash clichés and opinions of others were the norm. Few liked creative writing, in the form of essays or short stories. I was likely in the minority when I inevitably chose to write a story in our language paper, an option we were allowed in place of an essay. It was possibly the only thing I didn’t consider a burden during exams. If not pleasure, it gave me an escape from the humdrum of routine, the thrill of not having to write something from recall, from a pattern hardened by habit.

Here I was free to let my thoughts flow, craft something vague into a concrete form without fully knowing the final outcome. As I wrote, unaware of the mysterious process that let my words push the story forward, I was sometimes awed by the strangeness of not knowing the precise direction I was headed. It was as if the story had a life of its own, and drew me into writing it. Though I had a general idea of the denouement, rarely did I know how it would exactly conclude. Nonetheless, I was always keen to attempt it.

The fact that one can find hitherto unknown ideas during the process of writing is quite amazing in itself. Like Luke’s training with Obi wan, it’s akin to discovery of new things, new abilities, while rummaging inside a box with eyes closed.

“…let go your conscious self, and act on instinct”

But it’s a discovery accessible to all, not just the Jedi. For me, those times when I could suspend my conscious self to let my inner voice latch on to the unconscious and take me on a journey, however brief, into uncharted waters felt like an elemental step. A step closer to reality, to life itself.

Years later, I try to rediscover those times when I can. And hope to continue doing so for as long as I live. For during these moments, I am able to forgo my concern for rank.

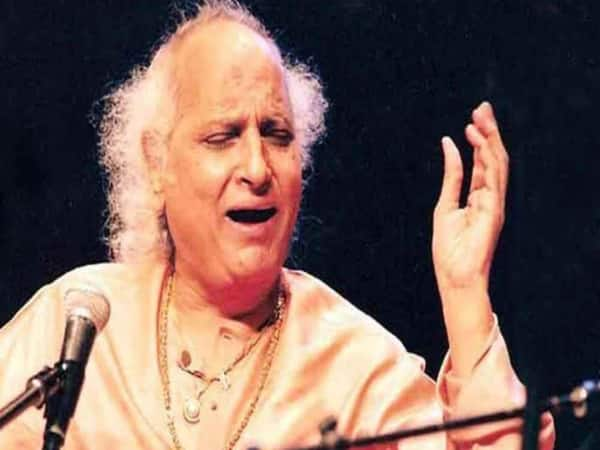

Pandit jasraj – how he chose to be a singer

Pandit Jasraj didn’t start his musical journey as a singer. As a boy, he was a tabla player and an accompanist to his elder brothers. The story of his decision to become a vocalist is fascinating, and shows the relevance of self-esteem and courage in success.

In 1945, he accompanied his elder brother Pandit Maniram to Lahore for a concert. Back then, tabla players had a relegated stature and usually not treated at par with vocalists. Jasraj was miffed on being offered a seat below the level of the singers during the performance. To pacify his little brother, Pandit Maniram let him sit alongside on the dais, and the concert went smoothly. The next day, however, a second event triggered Jasraj’s ire. During a discussion with a well-known musician who was visiting Maniram-ji and was being critical of another contemporary artiste, Jasraj disagreed, coming to the latter’s defense. But he was ridiculed by the critic as less knowledgeable, being a tabla player. That was the last straw. The young lad was deeply pained by two back-to-back humiliating episodes. He vowed to become a singer, and approached his brother Maniram to train him, who gladly agreed. A momentous decision that changed the course of his life. One needs raw determination at times to find one’s calling. This may evolve over a period of time, or, as in Pandit Jasraj’s case, in a flash. The important thing is to seize the moment. It can push us to touch our true potential. It spurred Pandit Jasraj on his musical quest and, through his sadhana*, touch divinity. Om shanti (ॐ शान्तिः)

*Sadhana (साधन) – Sanskrit: “Anything that is practiced with awareness, discipline and intention of spiritual growth can be considered Sadhana” Reference: https://www.yogapedia.com/definition/4994/sadhana

Apar Sansar by Ramprasad Sen

The great sage and mystic poet Ramprasad Sen composed many gems in the eighteenth century that are popular to this day in Bengal. In fact there is a special category called “Ramprasadi”, attributed to him, which falls under the broader Bhakti or devotional genre of music.

The great sage and mystic poet Ramprasad Sen composed many gems in the eighteenth century that are popular to this day in Bengal. In fact there is a special category called “Ramprasadi”, attributed to him, which falls under the broader Bhakti or devotional genre of music.

The song Apar Sansar¶, , or fathomless Sansar, the cosmos of creation, is a prayer to Ma Kali, the divine mother representational of universal female energy widely worshiped in India. In Bengal, there have been several great devotees of Kali, including the towering saint Sri Ramakrishna. Yogananda, inspired by Ramprasad, translated the song “Emon din ki hobe Ma Tara”, in the now well-known verse in his Cosmic Chants book titled “Will that day O come to me Ma”.

In Apar Sansar, Ramprasad invokes Kali to help him navigate the treacherous sea of Sansar.

Apar Sanar – Ramprasad Sen by Mystic Wanderer is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This boundless cosmos, there’s no way across

my dear Mother.

At your feet my faith, and all of my wealth,

protector from woes, be my savior

my dear Mother.

Beholding the waves, and the waters’ rise,

the body shivers fearing its demise.

A boat in your feet, I’m blessed to receive,

your humble servant, hold me together

my dear Mother.

The storms carry on, in ceaseless abandon

my body quivers, shaking in wanton.

Grant my hearts’ delight, Tara’s name is light.

Your name O Tara, essence of cosmos.

Eons slip away, Kali unattained,

Prasad laments that this life is in vain.

Sever worldly banes that refuse to wane.

Motherless, Tarini*, who to surrender?

my dear Mother.

¶ Sansar (संसार) – the world of change in Dharmic cosmology

*Tarini – Divine mother as savior

Hot chocolate

Hot chocolate by Mystic Wanderer is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Hot chocolate

runs down my gut.

My mind at ease,

shapes the thoughts

as they emerge,

flowing freely,

as words from pen

onto paper.

Tinkling spoons,

the sibilant

coffee machine,

barista calls –

“Tall mocha”! or

“Grande caramel latte”!

Another gulp.

A few more lines.

Then mind wriggles.

Vociferous.

Wants me to leave.

“You can’t write here,

what cacophony!

That kid is loud.

That woman in front

on her cell phone…”

My cup empty,

now it’s just me,

and the people,

the sounds and lights,

the radio,

ringing cell phones,

barista’s calls –

nothing between.

Unless I get

another cup.

Jana Aranya by Sankar / Satyajit Ray

I discovered Jana Aranya through Satyajit Ray, one of the most illustrious auteurs in cinematic history. Written by Sankar (Mani Shankar Mukherjee), it was a novel in a collection titled “Swarga, Marta, Patal” (Heavenly realm, Earthly realm and Lower realms, translated in resonance of the Lokas in Hindu philosophy). Another one from the collection, titled “Seemabaddha” (Company Limited) was also made into a film by Ray. These two films, along with “Pratiddwandi” (Adversary) are a part of the famed “Calcutta trilogy” – a set of stories based in the turbulent Calcutta (Kolkata) of the 70s.

Naxalism, an extreme form of communist idealism inspired by Mao and Guevara, started by Charu Majumdar in Naxalbari in North Bengal, had spread across the state. It had taken a hold of the imagination of the youth, particularly College and University students. They wanted a revolution, by violent means if necessary.

“They are neither afraid to die, nor to kill”

Naxalites unleashed brutal violence on people who, according to them, were a “part of the system”. Jhumpa Lahiri’s book “The Lowland”, though a work of fiction, describes the horrific events transpiring in Bengal, particularly Kolkata.

“They ransacked schools and colleges across the city. In the middle of the night they burned records and defaced portraits, raising red flags. They plastered Calcutta with the images of Mao.

They intimidated voters, hoping to disrupt the elections. They fired pipe guns on the streets. They hid bombs in public places, so that people were afraid to sit in cinema hall, or stand in line at the bank.

Then the targets turned specific. Unarmed traffic constables at busy intersections. Wealthy businessmen, certain educators. Members of the rival party, the CPI(M). The killings were sadistic, gruesome, intended to shock. The wife of the French consul was murdered in her sleep. They assassinated Gopal Sen, the vice-chancellor of Jadavpur University. They killed him on campus while he was taking his evening walk. It was the day before he planned to retire. They bludgeoned him with steel bars, and stabbed him four times.”

Eventually, the West Bengal state government went all out to quell the movement, eliminating many, often in the manner of a classic encounter killing – letting them loose in the pretext of a release and shooting them from behind. Similar to the manner in which the elder brother Udayan is killed in “The Lowland”.

“For a moment it was as if they were letting him go. But then a gun was fired, the bullet aimed at his back”

Unemployment was sky high, and the general mood extremely pessimistic. All three films of the Calcutta trilogy are in this backdrop, and while “Pratiddwandi” has a more direct connection to Naxalite movement, with the protagonist’s brother having joined it, the other two touch upon it tangentially. Nonetheless, one gains from cognizance of the social and political context of the times to appreciate these films.

Somnath Banerjee is fresh graduate, looking for a job. He and his friend Sukumar are among the hundreds of thousands looking to fill a precious few open positions in the grim employment scene. Unable to get a job, Somnath decides to start his own business as an order supply agent, or in plain Bengali – a “dalal”.

Someone who would supply the goods that an interested party wants to purchase. Hence the English title of the film, “The Middleman”, though Jana Aranya would literally translate to “Forest of people”, the human jungle one has to deal with.

He is aided by an experienced mentor, an old acquaintance Biswanath Bose, or Bishu babu, who provides the launching pad – office space, tips and some vital contacts.

When Somnath asks Bishu babu what he could supply, he says – “anything, from pins to elephants”, then goes on to narrate, in his own affable manner, an anecdote of how he managed to once dispose of an Elephant on behalf of a beleaguered businessman.

As Somnath gets initiated, he is helped by in particular by Adak. Somnath, according to Adak, he has an appeal that evokes sympathy in people. When Somnath asks if it’s his look of helplessness, Adak replies it’s because he’s still “straight”, and not learnt the tricks of the trade yet.

Adak introduces him to Natobar Mitter, who calls himself a public relations man, in reality a well-connected individual with deep contacts in the local business scene.

Somnath is about to land a lucrative contract that will assure him of a steady stream of income – supplying optical whitener for a textile factory. He meets the chief officer of the plant, Mr. Goenka, to push the deal through. But he is perplexed about the deal still not materializing, despite the right signs, and seeks Natobar Mitter’s intervention. Mitter uses his expertise to dig deeper into Goenka, and unearths that in order for Somnath to seal the deal, he has to provide Goenka with an escort. Somnath’s motivation falters, in a conflict of moral values.

He is finally compelled, after a discussion with Mitter, to sidestep his ideals and face reality.

Things get murkier when the prostitute he is trying to arrange for Goenka turns out to be none other than his old friend Sukumar’s sister, Kauna. Ray alters things a bit from the original story, where the sister isn’t aware of Somnath being the liaison. In the film, Somnath makes a final attempt to turn back, asking Kauna to return home. But she refuses. Though Somnath succeeds in getting the contract, he relents on his ideals. The “do not disturb” light outside Goenka’s hotel room fades into the perturbed eyes of Somnath’s father, waiting for his return in the semi darkness of a power cut. Somnath’s shadow precedes him as he makes his entry, symbolic of the shadowy business world he’s stepping into.

The film ends in irony as he announces his success, much to his father’s relief, as his sister-in-law, in whom he had earlier confided to the degeneracy of his trade, casts a circumspect gaze from behind the curtains.

The story provides a dichotomy between success and ideals that Ray likes to explore. He returned to this theme again in Shakha Prasakha (1990), his penultimate film, co-produced by Gerard Depardieu, where an ailing father realizes that the success of his own illustrious children have not been without compromise.

Although it has been over two decades having read the original story in Bengali, I do recall that it was highly readable, despite the complexity of theme. Ray’s film adaptation is equally approachable, but goes beyond. The narration, like many of his other films, is a chef d’oeuvre of composition.

The opening sequence in the examination hall, with Maoist graffiti on the walls and rampant copying in open defiance of the invigilators, transitions into a series of freeze frames of youthful faces in boisterous laughter, as if celebrating their ability to mock the system. As the opening credits continue to roll, Ray’s incisive orchestral score slowly unfurls in the background. One of the finest montages in cinematic history.

Pradeep Mukherjee portrays Somnath’s innocence and confusion with natural ease. Other notable performances are by Utpal Dutt, a doyen of Indian cinema, who plays Bishu babu, Somnath’s gregarious benefactor, and Rabi Ghosh as Natobar Mitter, the glib public relations officer – both seasoned actors. Ray cast them frequently in his films, including his final feature, “Aguntuk” (1991).

While the film’s cornerstone theme is the price of success, it also eulogizes entrepreneurship. One doesn’t always need a significant capital to get started. Enterprise and openness are keys to success, especially in adversity.

The film was made in black in white, in 1975, when most of the world had already moved on to color. In fact Ray had already switched to color in 1973 with Ashani Sanket, and the Feluda story Sonar Kella in 1974. Jana Aranya in b/w is an aberration, as all his films thereafter are in color. It’s unfortunate, in my opinion, that someone of the stature of Ray, who was already among the directorial luminaries of the world, was unable to find enough financing to make Jana Aranya in color. Or was it a conscious choice, in tune with the prior two films of Calcutta trilogy?

Suheldev by Amish

If you were to ask a High School student in India if she has heard of Suheldev, chances are that she would reply in the negative. Likewise for the battle of Bahraich. Not because Suheldev was a fictional character, or Bahraich a fictional location. This important king and a very significant battle are simply left out of school level text books, quite likely from College or University level text books as well. The reason is because in India, History is taught from the perspective of invaders. This tradition was continued by socialists and Marxist historians after independence, with nefarious intent. Sadly even now, after more than seven decades of independence from the British and a Nationalist government at the helm, no major attempts have been made to revise text books to include the Indian perspective. The importance of this retelling of History from the perspective of Indians is extremely significant to avoid a lopsided view. To borrow an African proverb, quoted often by Sanjeev Sanyal –

“Until the lions have their historians, tales of the hunt shall always glorify the hunter”

Thus, major leaders and events are hidden from the mainstream, Suheldev and the battle of Bahraich among them. To use Amish’s own words –

“Sadly, many of these heroes and heroines have been airbrushed out of our history books.”

Of late, thankfully, we have intellectuals like Sanjeev Sanyal and others playing a vital role in helping people rediscover these heroes. Amar Chitra Katha does its part. And a large part in being played by popular authors like Amish Tripathi, whose brand of historical fiction add color to these events and characters.

Suheldev is based on the historical character Raja Suheldo Pasi, who led an alliance of Indian kings to rout a large Turkic army in 1033, at the battle of Bahraich. Back then, India was the wealthiest economy in the world. It attracted invaders with the intent of conquest or plunder. Mahmud of Ghazni invaded India seventeen times and destroyed the Somnath temple. The Turks, however, were deterred after Suheldev managed to unite several kingdoms in resistance, and decimated the Turkic army led by Salar Maqsud, Mahmud’s nephew. The damage was so brutal that the Turks did not invade India for the next one hundred fifty years. That is how significant the battle of Bahraich was. And that is why it is all the more significant for popular fiction to unravel such heroes. More people will start asking questions after discovering these missing figures who played a vital role in the continuity of Indian civilization against relentless foreign invasions. Textbooks do not do them justice, but with their infusion into popular consciousness, Governments and committees will have little choice but to revise textbooks to include the likes of Suheldev, Rani Abbakka and Lalitaditya, so history is retold from the lion’s perspective, and not to always glorify the hunter.

In the book’s Foreword, Amish mentions that this book is a team effort, where the first draft is written by something called a “Writer’s Centre”.

“…the genesis of the story and the final writing is done by me, while the team drives the first draft”

This is a strange concept for me, as the first draft is most deeply connected to a writer’s consciousness. It’s the purest physical link between assimilation of ideas and their outward expression. To give it up to others would mean a lot, and I do not understand the motive behind such compulsion. But I’m not complaining, as long as the journey is good. And for this book, it’s been a very positive experience.

The work is cohesive and fast paced, with the right hooks to keep you engrossed. Don’t be surprised if you want to keep returning to finish it, or even wrap it up in a single sitting. That’s the desired outcome of a well written book, and this one achieves it exceptionally well. Through short chapters and a tight story line, its primary concern is to portray Suheldev’s emergence from a guerilla leader to one leading an Indian alliance to a resounding strategic victory against the Turks.

A theme of Indian unity is prevalent through the book. Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, Dalits, Kshatriyas forsake their differences to unite against a common enemy. This is essential for preserving the ethos of Indian civilization that the Turks were out to destroy. To quote Sanjeev Sanyal from “The Ocean of Churn” –

“The Turks were unbelievably cruel towards Hindus and even fellow Muslims, but they seem to have reserved their worst for the Buddhists. One possible explanation for this is that they themselves had converted to Islam from Buddhism relatively recently and felt that they had to prove a point”

The narrative is also quite filmic, maybe with deliberate intent. Gory battles, of which there are many, are vividly etched. There is also a hint of romance in the otherwise bloody tale. And an intrigue about Aslan that keeps one guessing until the end. All these elements and a strong sense of patriotism prevalent throughout the book, could be easily espoused to a screenplay, and a Bollywood hit in the hands of a competent director. Perhaps brand Amish already has that in mind. Har Har Mahadev. And a few years from now, if you were to ask a High School student in India if she has heard of Suheldev, you know the answer is likely to be a resounding “yes”.